Once more I’m in the unhappy position of writing harsh things about someone whose work otherwise has my unqualified admiration…

Readers may recall my earlier piece on Whitney Terrell’s ‘The King of Kings County,’ a brilliant novel of manners set in Kansas City’s upper crust.

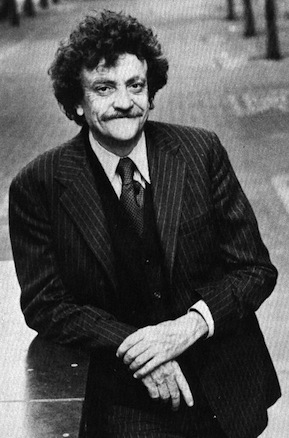

This time I’m squaring off against a critic named William Deresiewicz who wrote an essay a year ago in The Nation on Kurt Vonnegut. (The essays he penned on Joseph Conrad for The New Republic and on elite colleges for The American Scholar are so good I have shared them with many friends and acquaintances.)

The fact that the Vonnegut article appeared in The Nation, a publication that has never come to grips with its Stalinist past, was an early warning sign. The choice of Vonnegut for reappraisal was itself also suspect, and may have had more to do with nostalgia by Mr. Deresiewicz, born in 1964, for a sixties he never experienced than measured literary judgment.

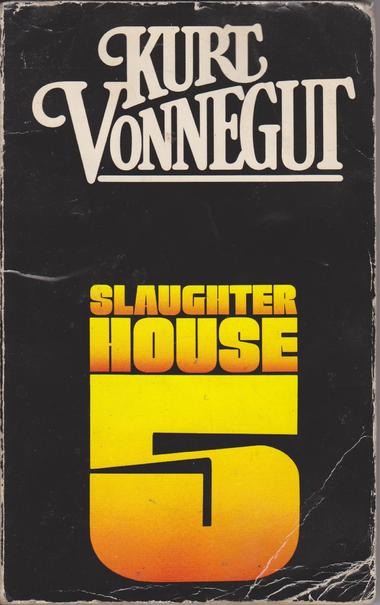

As I told my son, when forcing him to watch a video of “Billy Jack,” you have to see for yourself how bad that era was. It was in that spirit that I reluctantly agreed to read “Slaughterhouse Five” for a book club I belonged to, which is also how I came across The Nation essay by Deresiewicz.

As I told my son, when forcing him to watch a video of “Billy Jack,” you have to see for yourself how bad that era was. It was in that spirit that I reluctantly agreed to read “Slaughterhouse Five” for a book club I belonged to, which is also how I came across The Nation essay by Deresiewicz.

Mr. Deresiewicz is honest enough to dismiss most of Vonnegut’s writing pre-Slaughterhouse as juvenile and inchoate in its message. He also notes the elements that mar those prior efforts, a sort of dime store nihilism, coupled with moral relativism on steroids (“If even Nazis cannot see themselves as evil, then how can we be sure that we aren’t evil, too?” This may have sounded profound in 1971 in a college dorm room at 2:00 a.m. under the influence of cannabis sativa but now it just sounds moronic.) Deresiewicz, however, insists that it is these very qualities that make Slaughterhouse Five “an exquisitely realized work of art.”

The only thing he can point to in “Slaughterhouse Five” that gives it any sort of credibility is that it reflects Vonnegut’s own experience as an American POW in World War II who survived the fire-bombing of Dresden, Germany.

That ain’t chopped liver, any more than Stendhal’s witnessing Waterloo, or James Jones’s presence at Pearl Harbor. However, it’s what you do with that credibility now that you’ve got the reader’s attention that ultimately matters, not whether you were entitled to it in the first place.

And it’s precisely because “Slaughterhouse Five” is so much Vonnegut’s own story that it fails so objectively. For the undeniable truth is that Kurt Vonnegut, and his alter-ego in the book, Billy Pilgrim, are distinctively unsympathetic as individuals.

And it’s precisely because “Slaughterhouse Five” is so much Vonnegut’s own story that it fails so objectively. For the undeniable truth is that Kurt Vonnegut, and his alter-ego in the book, Billy Pilgrim, are distinctively unsympathetic as individuals.

Vonnegut’s world is “mad, indifferent, arbitrary and cruel.” All human effort is doomed to failure. There are no absolutes except the “universal urge to self-delusion.” In other words Vonnegut himself is the classic intellectual. He loves “The People,” it’s just individual human beings that he despises. Throughout the book he makes innumerable snide comments about ordinary people, i.e. one woman character is dismissed as having “a 103 IQ,” another as “just a high school graduate.” People are mocked for lowbrow tastes, e.g. ‘Almond Joy’ and ‘Three Musketeer’ candy bars, ‘Barca-Lounger’ chairs, etc.

Vonnegut, the product of a wealthy and educated background, is very angry and frustrated with the American working class, as embodied in the enlisted men he encountered in the army and excoriated in “Slaughterhouse Five” (“a mass of undignified poor”).

They should be angrier with their plight! They don’t blame the rich for their suffering! They insist on taking personal responsibility for their situation! They still believe in rising through hard work! They worship success and look up to those who have risen! Their real crime, of course, is that they have not Questioned Authority (as the bumper stickers in most college towns say) and replaced The Establishment with people like himself-intellectuals.

It never occurred to Mr. Deresiewicz to note that “the subversion of books like Catch 22, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “the psychedelic space wisdom of books like….Jonathan Livingston Seagull” look pretty lame in hind-sight. (He is happy to include Vonnegut in that confederacy of dunces with no sense of irony.)

I thought of Vonnegut, Heller, and the collective wisdom of the sixties a few years ago when I was leaving a movie theater after seeing Steven Spielberg’s D-Day epic, “Saving Private Ryan.” It was in East Hampton, New York, an affluent resort town with a substantial Jewish population. Two young men were filing out right in front of me, when one turned to the other and said; “Remember, all those people died for absolutely nothing!” After all, what if they “gave a war and nobody came?” It might be a world ruled by the Hitlers, Stalins, Maos, etc., but who are we to say we’re any better? This is truly the legacy of Vonnegut and his ilk, not just the cynicism and sordidness of their books. Someone as intelligent and well-informed as William Deresiewicz should know better.

I thought of Vonnegut, Heller, and the collective wisdom of the sixties a few years ago when I was leaving a movie theater after seeing Steven Spielberg’s D-Day epic, “Saving Private Ryan.” It was in East Hampton, New York, an affluent resort town with a substantial Jewish population. Two young men were filing out right in front of me, when one turned to the other and said; “Remember, all those people died for absolutely nothing!” After all, what if they “gave a war and nobody came?” It might be a world ruled by the Hitlers, Stalins, Maos, etc., but who are we to say we’re any better? This is truly the legacy of Vonnegut and his ilk, not just the cynicism and sordidness of their books. Someone as intelligent and well-informed as William Deresiewicz should know better.

Taking Vonnegut too seriously is a job left to those able to ride Mike Fox’s DeLorean back to the future in bell bottoms, fat white belts and shoes with goldfish in them.

Reading this review, I remembered my college days in the 70’s, where the apotheosis of Vonnegut’s oeurve kept time to Blood, Sweat and Tears. Come on Sutherland, the guy came up with “Chronosynclastic Infundibulum”. A place where Harley, Glaze and S. I. Hayakawa agree on syntax, form and content reading Joyce in a medical waiting room for gender reassignment.

This quote in Deresiewicz’s review, smacks of one of my very favorite themes, Laplace’s Demon.

“Rumfoord’s religion (with Constant as Christ) is called the Church of God the Utterly Indifferent. In the novel’s context, the notion comes as an immense relief. Everybody thinks he has free will, and everybody’s secretly controlled by someone else. Constant, on Mars, is controlled by Boaz. Boaz is controlled by Rumfoord. Rumfoord is controlled by the Tralfamadorians, and so is all of human history.”

We’re the fu*kin Borg baby, resistance is futile.

He seems to think KV takes responsibility for lifes vicissitudes.

“This is high Greek stuff. Our moral beings are not ours to rule, yet we are accountable for them all the same. Tragedy means that, in the end, you do not question what’s become of you, because you know that you deserve it.”

That actually smacks more of mysticism and Eastern thought than Greek stuff, but I am ok with it.

His take on Slaughterhouse Five is dead on, imo.

“The novel isn’t about flying saucers, and it isn’t finally about Dresden, either. The raid gave Vonnegut the peg on which to hang the book and goaded him with a sense of occasion—of having stumbled into precious literary material—but as he had lamented to himself for years, he hadn’t actually seen it, safe in the deep, sealed basement of the slaughterhouse. Only once he realized that his true subject was his own long ordeal as a prisoner of war—fleeing, starving, packed for days in a cattle car, put to slave labor, almost killed by German guards and American planes, watching his fellow prisoners die all around him—was he able at last, I believe, to write the book.”

Vonnegut belonged to another time when I was young and liberal, maybe you were too. I am not embarrassed, I am sorry the world wouldn’t bend to the will of those folks singing Kumbaya and walking out of “Private Ryan” with the hope that some new American weltanschaung can spring forth from the actual real time American weltschmerz.

You Mr. Sutherland are easily the finest new talent here in this room and have arrived to rave reviews, justifiably so.

Keep your head up pal, Vonnegut was a hoot.

As of all you said, I was most pleased with the proper use of the term “goad”. I grow weary of the people “getting someone’s goat” or goating them into doing something. But I don’t suffer fools/Harley well.

I think he was a decent read and entertaining. If you go taking what he wrote literally, sure I could see problems. I think his portrayal of the firebombing was fine considering his circumstances. I mean, he went through a pretty horrific ordeal, if he wants to write about it as sci-fi, let him. I don’t go reading Vonnegut for heady philosophical stuff, that’s for sure.

Barry Switzer’s Bootlegger’s Boy is the best American autobiography since US Grant’s. Other than that I think books are full of lies and TV is twice as fast.

But seriously…

Check out Player Piano, Galapagos and Breakfast of Champions. For as personal of a story that Slaughterhouse 5 was I agree with the author that it was very emotionally hollow. Like many good books that were talked up to be great ones you leave expecting a bit more. The absurdity of GE, the absurdity of the Green movement and the absurdity of happiness through consumption were better topics for his nihilism than WWII.

Gentlemen- I generally agree that it is a mistake to read too many metaphysical implications into forms of popular entertainment like science fiction or satire,genres which much of Vonnegut’s work qualifies under. The problem is that not only did the author begin to take himself seriously but so did much of the rest of the world.After all, teaching positions at the Iowa Writers Workshop and Harvard still carried a lot of weight. Cameo roles in Hollywood movies,alas, carry even more if your goal is to be thought of as sage and artist/hero. I think the different reactions to Vonnegut are not just a generational thing,but a reflection of different age cohorts within the boomer generation. My buddies who graduated from college in ’68 & ’69 think the era was wonderful,those of us who got out in ’74 & ’75 find a lot of it acutely embarassing.

In the 70’s, KV was taken as seriously as Solsenitzen, no doubt.

So the man was cynical and disillusioned, wouldn’t you be a little too after what he went through?

Sure, but what I am saying, is that in the 70’s in college, when I attended college, KV was taken very seriously.

Oops, Solzenitzen.

Isn’t BHO just a genetically modified version of KV?

So it goes.