Lincoln Kirstein was a brilliant American artistic impresario who founded everything from the Hound & Horn (the foremost literary magazine of its era) to the New York City Ballet. When he was at graduate school at Harvard in the early 1930’s, he got a grant from the university to locate a lost Renaissance masterpiece, thought to be forgotten in some local church in Europe.

Lincoln Kirstein was a brilliant American artistic impresario who founded everything from the Hound & Horn (the foremost literary magazine of its era) to the New York City Ballet. When he was at graduate school at Harvard in the early 1930’s, he got a grant from the university to locate a lost Renaissance masterpiece, thought to be forgotten in some local church in Europe.

Kirstein and a buddy managed to burn through most of the money traveling one summer, only to discover that the painting in question was in the Municipal Gallery of Worchester, Massachusetts the whole time. (Less than fifty miles from Cambridge!)

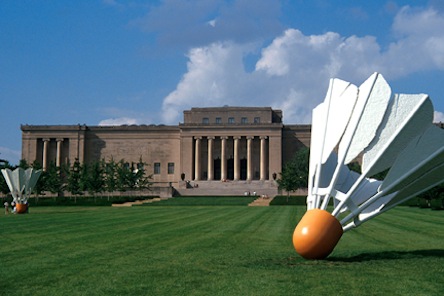

I thought of this story when I remembered that one of the world’s greatest artistic treasures can be found here in Kansas City (and has been here since 1952, the year I was born!) I’m speaking, of course, of Caravaggio’s 1604 painting of St. John the Baptist at the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

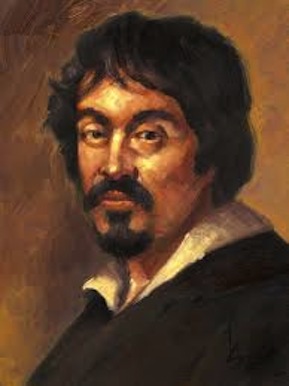

Born in 1671 in Caravaggio, Italy, the village near Milan whose name he took, the painter Michelangelo Merisi trained under several older artists before going out on his own. With two cardinals as his patrons, he succeeded in getting important commissions in Roman churches.

Caravaggio’s paintings revolutionized art and were quickly recognized for their impact throughout Europe. They represented a definite break from the formalism of the Renaissance and the stylized results of Mannerism. Critics have called his works “naturalistic,” both because of the way they were painted and his choice of subject matter.

Caravaggio’s paintings revolutionized art and were quickly recognized for their impact throughout Europe. They represented a definite break from the formalism of the Renaissance and the stylized results of Mannerism. Critics have called his works “naturalistic,” both because of the way they were painted and his choice of subject matter.

Terms such as “raw, immediate, and palpable” have been applied to his paintings. Caravaggio was different from predecessors in that he painted from live models, without prior line drawings to work from. He was also a pioneer in using a style of starkly contrasting light and dark known as “tenebrism,” from the Latin for shadows, “tenebrae.”

This device of a light piercing a dark background is used to illustrate a spiritual awakening in the characters portrayed. The experience of faith is outward and visible.

The Kansas City St. John The Baptist is part of a series of seven different paintings of that Saint. (The Nelson-Atkins work is fourth in the sequence.)

The painting here has the artist’s characteristic stark contrast between light and dark. It is brooding and bleak in tone, in keeping with Caravaggio’s own troubled personal history. (He left Rome for exile after killing a man in a dispute over a card game shortly after this painting was completed, a crime which even powerful protectors within the Church could not shield him from the consequences of. He is thought to have been killed while attempting to return, after years in Malta and Naples.)

Interestingly, there was very little in the way of the overt symbolism associated with this particular saint by prior artists used here. Nor was there the open sensuality and eroticism we think of with Caravaggio’s other young male models, who border on the “rough trade” that I’m told could only be obtained here locally at the Liberty Memorial in years past. The seated half-figure, solitary and lacking any allegorical props, has what the critic Peter Robb called a “feeling for the drama of human presence.” Many see it as strong evidence that Caravaggio opened the door to the Baroque. The painting was not just intrinsically important but hugely significant for the change it ushered in.

The story of how the painting got to Kansas City is also revealing.

The story of how the painting got to Kansas City is also revealing.

The late Milton McGreevy, a Nelson-Atkins trustee, and his wife and daughter were touring Europe in 1952. They were shopping in London on Bond Street and dropped in without an appointment to Thomas Agnew & Sons, art dealers. When they saw the painting they immediately wired Kansas City and got the authority from the other Nelson trustees to buy it. I can think of no other major gallery, then or now, that gave its lay patrons such freedom to act on its behalf, without the careful direction of and oversight by professional staff. This is a tradition that has continued to this day, with happy results for our city.

Go down to 45th & Oak and see for yourself.

The Nelson is one of the few things, the Kansas City Symphony being another, that continues to draw me back to visit KCMO. Both are world class and deserve greater attention than they get.

I love the Nelson. Great story.

I know everyone makes fun of those shuttlecocks, but I think they are so cool.

I think E. Buzz Miller has a few Titian paintings he could sell the Nelson.